by Richard Stubbs

The bezzel is the period that any embezzlement remains undisclosed. Galbraith used it to explain how, over this period, there is a positive wealth effect, as both the embezzler and the embezzlee believe they possess the embezzlement.

In an entertaining speech, Charlie Munger considers the functional equivalents to the bezzel which he calls the "febezzel". The febezzel need not be illegal, but it has the same effect of creating the illusion of wealth where there is none.

Unfortunately, you do not need to look too hard to find potential examples of the febezzel in financial markets. Reported profit, perhaps, is a good start.

An accounting profit is just a best guess of the economic profit of a business in any given period. The economic profit of a business is the residual after all other claims on revenue, including opportunity costs, which can be proxied with the cost of capital. It is, in effect, the change in intrinsic value of a company for a given period. Accounting profit is often a relatively good guess, but it can be a febezzel candidate when calculations become complicated. If accounting profit overstates the economic profit of a company, its share price might also overstate its intrinsic value, creating a short-term illusion of wealth for the holder of the equity in that company.

Take banks, for example. Due to the highly leveraged nature of a bank’s balance sheet, estimating the profit in any one year is very difficult. Fluctuations in the market value of a bank’s assets and liabilities makes an asset valuation approach to profit calculation tremendously complicated and volatile. Cash-based profit calculations, while potentially more stable over a period, can be equally misleading. Cash profits can be easily increased in the short-term by lending to lower quality borrowers at higher interest rates. This looks fine while the interest is being paid, but there might be little or no hope of seeing a return of most of the principle. Some of New Zealand's finance company collapses are a good example of this.

Perhaps the historic tendency for the banking industry to suffer from repeated bank crises is due to the overstatement of profits. This would result in the gradual erosion of the bank’s economic capital. At some point, this erosion would be so great that it could no longer be hidden in accounting numbers, and the bank would be forced to declare massive impairments. Because banks generally follow similar practices, weakened banks can often suffer write-downs at a similar time, resulting in systemic risk.

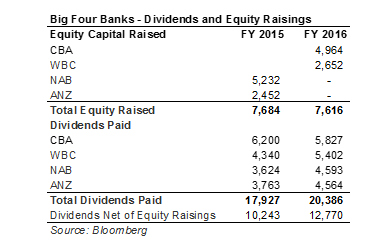

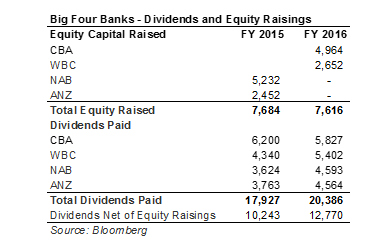

Over the last two years. the four large Australian banks have paid out AUD$38bn in dividends, more than 10% of their combined market capitalisation. But they have also raised AUD$15bn in new equity capital. Would it not have been more cost effective to pay a lower dividend? Organising a capital raise incurs a substantial amount of cost in fees and management time. I am sure the banks’ advisors would argue that it is tax efficient to pay a dividend to make use of franking credits. But if the tax profit is an overstatement of the economic profit, this is illusory, as too much tax has been paid in the first place.

In our opinion, a high dividend can be just another iteration of the profit febezzel. Indeed, if profits are overstated then too much cash capital will be being returned to shareholders. This issue is currently compounded by the growth in dividend-hungry ETFs that will blindly buy high-dividend-paying companies and quickly dump those that lower or stop dividends.

Agency theory will tell you that when executive compensation is linked to profits and share price, those executives are likely to prefer accounting practices that are supportive of high accounting profits and dividends, even if it is to the detriment of the long-term intrinsic value of the company. In a 2005 survey of 401 financial executives by Duke University’s John Graham and Campbell R. Harvey, and University of Washington’s Shivaram Rajgopal, a startling 80% of respondents said they would decrease value-creating spending on research and development, advertising, maintenance, and hiring to meet earnings benchmarks.

It is our opinion that an investor must be wary of an accounting profit number in proportion to its complexity. Banks are at the top of the list.

So, when might you consider investing in a bank? In our opinion, banks are risky long-term investments. The best time to buy one is probably after a crisis which has seen the replacement of an exuberant Board and management team … and a recapitalisation.

The following commentaries represent only the opinions of the authors. Any views expressed are provided for information purposes only and should not be construed in any way as an offer, an endorsement, or inducement to invest. All material presented is believed to be reliable but we cannot attest to its accuracy. Opinions expressed in these reports may change without prior notice. Castle Point may or may not have investments in any of the securities mentioned.

Richard is the co-founder of Castle Point Funds Management. Previously he was Head of Equities for Tower Investments in Auckland.

| « Quantitative investment styles, and when they perform | Responsible investing: Is there a cost? » |

Special Offers

No comments yet

Sign In to add your comment

© Copyright 1997-2026 Tarawera Publishing Ltd. All Rights Reserved