In the eighteenth century, Adam Smith (perhaps the father of free market economics and whose face now rather inappropriately adorns one of the UK's bank notes - the current regime being anything but laissez faire in its attitudes to the economy) suggested that the collective result of numerous individuals following their own economic self-interest rates would underpin economic growth and therefore benefit society as a whole.

Some three hundred years later, Spielberg's ‘trailer' for the inevitable sequels that were to follow the first Jurassic Park movie noted that nature would always find a way to perpetuate its species. The same seems to be true of investment bankers.

We believe that there is mounting evidence that the remains of the US investment banking sector and its counterparts in the Euro Zone, UK and Japan are dusting down their asset growth models of the mid 2000s and once again expanding their balance sheets with increasing enthusiasm.

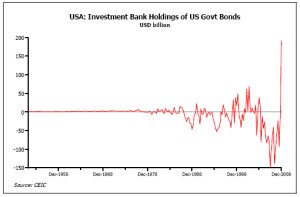

Although hard data on their activities is hard to acquire, we are beginning to see the foot prints emerge of an intriguing paper-trail. For example, in late 2008, the US investment banks apparently borrowed at near zero interest rates more than $150 billion (at an annual rate) from the US central bank, the Federal Reserve. The investment banks then used these funds to purchase Government Bonds, a safe asset that yielded considerably more than the banks' heavily subsidised cost of funding.

For the government, this was a happy situation: the purchase of such a large quantity of bonds by the formerly defunct investment banks significantly helped to ease the financing burden of the rapidly expanding budget deficit and the ‘extra' interest income that the banks earned in this transaction will undoubtedly have helped to recapitalise their highly compromised balance sheets.

Therefore, for all concerned this was a happily symbiotic relationship and in some sense there was even a pleasing circularity in the arrangement - the banks were providing the funds with which the government was in turn using in its efforts to recapitalise the banking system.

Unfortunately, it is the nature of investment bankers (who may be avaricious but who are also very smart) to look for better returns whenever possible and doubtless it did not take these institutions long to realise that they could better the returns that they were earning on Treasuries simply by investing in lower quality credits.

Consequently, we believe that in the middle part of the first quarter of this year, the investment banks took their holdings of Treasuries (which they had purchased with the Fed's money) and used them as collateral in order to borrow yet more money from a variety of lenders, even including the Federal Reserve itself.

It appears (although we have no conclusive proof as yet - only circumstantial evidence) that the investment banks then embarked on a process which saw them leverage the funds that they had raised in this fashion through the derivatives markets into a variety of risk markets, including the higher yield bond markets.

Indeed, we suspect that it has been these flows from the investment banks that have underpinned not only the recent improvement in the US's domestic corporate bond markets but also in international bond markets as well.

For US companies, this re-vitalisation of the private debt markets has been most fortuitous. As recent data releases have emphasised, both conventional bank lending flows to the corporate sector and the commercial paper markets have remained exceptionally weak, thereby implying that the only still-functioning credit channel to the corporate sector has been the bond markets.

Without the continued activity within the longer term bond markets, the US corporate sector's financial predicament would doubtless have been very much worse over recent months and therefore we can argue that the activities of the newly resurgent investment banks has exerted a positive impact on the real economy as a whole, just as Smith predicted that such profit-maximising behaviour would.

Moreover, it also appears that the resurgent bond markets have helped to revitalise international capital movements in Australasia and the emerging markets. Certainly, Australia, New Zealand and many emerging markets have witnessed a marked improvement in their external capital account transactions and this return of foreign capital may have helped to foster an easing of effective credit conditions in some of the economies concerned (although probably not in New Zealand it seems), an event which will have been at least a little supportive of growth prospects in these economies. Moreover, we suspect that it is these flows which have been behind the recent appreciation in many of the recipients' currencies, including the AUD and, to an albeit lesser extent, the NZD.

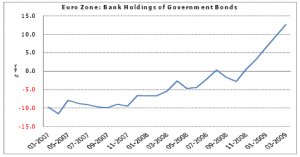

Meanwhile, in Europe and Japan, there is also growing evidence that the investment arms of the commercial banks have also been using their respective central banks' offers of cheap funding to acquire rapid acquisitions of domestic government bonds and we find that, in both regions, the banks' appetite for public sector bonds has actually exceeded the supply of new bonds.

Consequently, the European and Japanese banks have been creating a ‘net' injection of funds into the bond and financial markets in general and we believe that this will have also proven beneficial to the countries concerned. Indeed, various sources suggest that the European corporate bond markets are currently booming and we suspect that this improvement in funding conditions owes much to the return of the banks to the bond markets over recent months.

In some senses, the resurgence in the investment banking sector has proved both Smith and Spielberg right. The investment banks have managed to perpetuate their former business models and thus maintain themselves and their profit growth (witness their recent strong earnings reports) despite their brush with extinction only a few months ago and, in so doing, they have opened what in reality is a new and beneficial transmission mechanism into the real economies for the Fed's and others' expansionary policy regimes.

Moreover, we also suspect that it is the sheer weight of money involved in these flows that has allowed global risk markets, such as the equity markets, to rally over recent weeks, despite the still mixed tone of the data from the real economies.

Certainly, although equity and other risk markets have been able to take some encouragement from the recent improvement in the various global production data series that are available, it remains the case that the level of end-user demand in much of the developed world for this extra production remains very limited indeed, a situation that could cause production trends to weaken once again before year end. Therefore, we suspect that it has been the improvement in liquidity trends described above that has played the primary role in the recent improvement in financial market conditions.

Unfortunately, there are also a number of problems associated with the current situation. Firstly, many central bankers regard many of the derivative instruments in which the investment banks are now dealing as being the next potential ‘weapons of mass destruction' and therefore they are uneasy with many aspects of the process.

At the same time, it is equally apparent that many politicians and members of the press are unhappy that the investment banks are now making huge sums of money again, so soon after they were rescued with public funds. Consequently, there is now a move in some central banks - possibly including the US Federal Reserve - to provide less liquidity and fewer credit facilities to the banks and it is already apparent that this change in official attitudes is beginning to effect financial market conditions.

Indeed, one of the most striking features of the last few weeks has been the rise in US Treasury bond yields and we would firmly place the causation for this event on the signs that the Fed has become less generous with regard to its dealings with the investment banks. Of course, we suspect that the Fed is not pleased that long term yields in the economy are rising and it will probably step up its own purchases of Treasury bonds as a result but the fact that yields are nevertheless still rising suggests to us that, on a net basis, global liquidity conditions are tightening at the margin, a factor that could soon act to constrain the current rally in risk assets and high yielding currencies around the world.

At the very least, we would urge investors in equities and in high yielding currencies such as the NZD to pay close attention to the gyrations in the US T bond market at present - continued weakness in US bond markets could yet have significant negative implications for world markets.