Market Review: February 2010 London Commentary

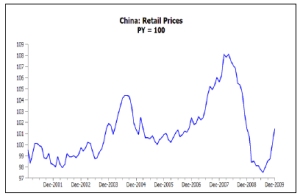

Somewhat unconventionally - and rather unpopularly we suspect - we remain bearish on the outlook for near term inflation rates in much of the global economy, based primarily on the current adverse trend in Asian export prices.

Friday, February 12th 2010, 10:57AM

Will Long Term Borrowing Rates Collapse?

Quite simply, we believe that the recent appreciation of many Asian and Latin American currencies, together with India and China's rapidly accelerating domestic inflation problems, are leading to a rise in consumer traded goods prices that has the ability to create higher inflation in the developed world, particularly given the West's post globalisation increased reliance on supplies of goods from these areas.

At the same time, weak comparison periods, rising taxes and other public sector charges can also be expected to add to reported inflation rates. Hence, as the UK has already demonstrated, inflation rates may surprise on the high side in the near term despite what are still extremely weak global growth trends.

To some, it may seem odd to some to report ‘weak global growth trends' when the US has just reported a 5.7% annualised rate of GDP growth but we have a number of reservations over the use and interpretation of this particular number. While the reported stock building component within the GDP data appeared roughly in line with our expectations, the import component appeared rather too low to us, thereby suggesting the potential for a downward revision to the overall GDP growth rate from this source.

Moreover, in the production-based version of the data, the first estimate will have been heavily reliant on large company surveys and we suspect that Ford's 30% rise in Q4 output may have been disproportionately influential in the formation of this first estimate of GDP. As more data becomes available from the still very weak smaller company sector, we suspect that there may also be more downward revisions to the data. However, these essentially technical issues do not form the basis of our concerns over the use and interpretation of the data.

From its peak in mid 2008, US GDP has fallen by around 2% but total employment in the economy is down by almost 6% (hence the current wave of optimism over both profits and productivity). However, US productivity growth has generally been estimated to be around 2.5% per annum over the last decade or so and therefore it would seem that the level of employment relative to the level of GDP is currently ‘about right'.

In the industrial sector, in which much of Q4's growth is reported to have occurred, total output is down by 10% and employment by around 12% from their respective peaks, a situation that actually suggests a rather disappointing productivity performance by the sector. The conclusion that we draw from this analysis is that the labour market has not been particularly weak given the level of decline in production and, furthermore, that during the middle part of 2009 (during which GDP was somewhat lower) the labour market may actually have been a little stronger than was justified by the then current level of economic output.

From this, we can infer that companies perhaps ‘hoarded' labour during the worst part of the crisis in early 2009 so that they would have access to this same labour once thede-stocking phase ended, which it now appears to have done. Consequently, the supposed end of the US de-stocking process has not generated jobs growth in the economy, not only because we suspect that many of the inventories that were acquired in Q4 were sourced from abroad, but also because those that were sourced domestically were more than likely created by workers who had already been retained for just such an event.

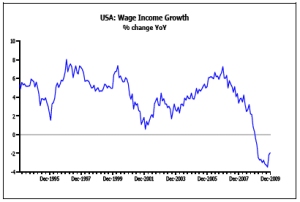

As a consequence of this seemingly complicated chain of events, it now appears that inventories relative to shipments; sales relative to production and perhaps imports; and production and employment levels are all now roughly aligned at mutually consistent levels. More importantly, it explains why the fourth quarter's perhaps superficially strong growth (much of which was simply the arithmetic result of the non-farm inventory component moving from a large negative to a neutral number) failed to generate wage income growth in the economy. It seems that the increase in domestic production associated with the ending of de-stocking was relatively modest and it utilised existing stocks of employed labour, with the result that it provided little or no income growth for the household sector.

This lack of nominal wage income growth is of course crucial for the outlook for 2010. In 2009, wage incomes declined for the average household but the sector was given on average a 3-4% boost to their disposable incomes through tax rebates, lower interest rates, social security payments and other transfers.

It was this ‘topping up' of household financial resources that allowed consumers to both spend a little more in the second half of 2009 and to save more.

Perhaps more importantly, the fact that households were able to spend and save more despite earning less from companies explains why companies were themselves able to earn more profits. In essence, that part of the government's transfers to the household sector that were not saved ultimately ended up as increased profits for companies - a scenario straight out of Keynes's theories in the early 1930s. However, as we look into 2010, there appear to be few if any tax rebate cheques left to be sent out and, as the central banks have begun to exit their extraordinary Quantitative Easing Policy Regimes (QEPs), fiscal policy is naturally coming under pressure to tighten - as we have seen around the globe in recent days.

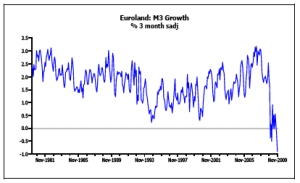

It is perhaps a little known fact that the various QEP's implicitly funded at least 90% of the major economies' budget deficits over the course of 2009 but now that the central banks are signalling their intent to exit or suspend their QEPs, governments face a severe funding problem that has been made even worse by many commercial banks selling their own existing bond holdings ahead of the official suspension of QEPs. Presumably, the commercial banks have not wanted to be ‘caught out' holding large bond positions when QEPs end in the way in which they were in previous QEPs exit periods, such as 1994 (FRB) or 2006 (BoJ).

Hence, we have seen heavy selling of government bonds by commercial banks over recent weeks and we believe that it has been this event that has both reduced reported money growth around the world and removed liquidity from risk markets.

Certainly, we believe that while Greece and other countries' funding problems may be much of the root cause of the current turbulence in financial markets, the actual catalyst for the events of recent days has been the fact that the ECB, BoE and FRB have already in effect ended their QEPs, thereby causing global liquidity growth to plummet.Time and again throughout history, we find that quasi-QEPs have been able to obscure poor fundamentals and generate asset price booms but whenever they have been removed, the anaesthetic that they provide has worn off and the problems in the underlying economies have been revealed once again, be they the Euro Zone PIGS' awful competitiveness and fiscal positions or Japan's chronic lack of supply side mobility.

Returning to our central theme of household income growth, we find that the enforced tightening of fiscal policy now occurring coupled with the prospects for continued weak or negative wage income growth (implied by our productivity analysis above) implies that households in the US and elsewhere will experience very little in the way of nominal disposable income growth in 2010. At the same time, the rise in import prices (and food and fuel prices) currently occurring will act as a "tax" on their already meagre resources.

Therefore we cannot help but feel that consumer discretionary spending growth in 2010 will have to be very weak, unless the household sectors' savings rate declines significantly. However, in order for the savings rate to decline, households will have to ignore their weak balance sheets and be able to access sufficient credit to achieve the drop in savings; events that while not impossible are improbable. We therefore suspect that, based on current trends, consumer spending growth in 2010 will be well below consensus estimates and as a result we can expect no new re-stocking or CAPEX cycles either. Far from a 2-3% GDP recovery in 2010, we suspect that the global economy will barely move forward, presumably to the chagrin of the politicians.

Indeed, given this poor growth outlook and the already visible effects of the QEPs' exit strategies on asset markets, we can see a case for a re-easing of monetary policy later this year once China's economy stops exporting inflation (which if China's own monetary tightening is as effective as we believe it may be, could be as soon as 2010H2). In many senses, the central banks have already achieved what they set out to do when they first mooted ending their QEPs: some form of fiscal discipline is being imposed on reluctant governments; asset markets have cooled and with them the threat of new bubbles; and some precautionary monetary action has been taken to ensure that imported inflation dos not trigger new domestic inflationary cycles.

Consequently, in a few months time - and certainly by midyear - we would envisage central banks becoming rather more pro-growth and therefore we expect to see them making some very dove-ish noises that are designed to encourage leveraged institutions back into the bond markets. Such an event would likely to be beneficial to not only the bond markets and interest rate trends, but ultimately to all risk markets as well.

Admittedly, in the near term, we see the determination of government bond prices in general being the result of a ‘fight' between two opposing camps.

The first camp consists of the selling pressure in bond markets being generated by the mechanical effects of banks' unwinding of the QEPs coupled with growing fiscal policy concerns amongst investors and the unwelcome intervention of higher reported inflation rates. In the second ‘buying' camp, we have fears of a global relapse and declining global risk appetite. Our preference would be to expect higher rather than lower yields in the near term (although this position has become rather embattled of late) but ultimately we expect a 2010H2 return of pseudo QEPs that sees bond yields reach new lows against the background of a still weak global economy. Intriguingly, we suspect that equity markets might also find this outcome quite appealing, although perhaps not in the very near term.

Andrew Hunt

International Economist, Tyndall

London

| « Mercer's top 10 investment trends for 2010 | Overhaul of Financial Advice » |

Special Offers

Commenting is closed

| Printable version | Email to a friend |